As the Union Army commanders dithered over attacking Confederate-held Norfolk and Portsmouth, the Union Navy reeled under the attack of CSS Virginia.

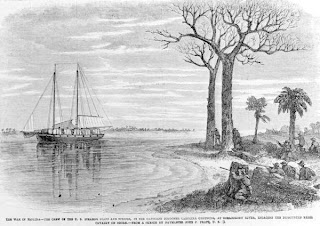

What were steady rumors flowing across Hampton Roads about the Confederates building a new kind of warship out of Merrimack became published fact when a New York Herald reporter, Bradley Sillick Osbon with extensive service in the Navy, rowed “a Hellgate pilotboat” with muffled oars from Fortress Monroe to the naval shipyard.

Drawing close to the vessel on a foggy night, “I fixed her outlines and proportions in my mind and returning undiscovered wrote a description of her for the Herald, and made a sketch for Harper's Weekly.” Osbon reported his findings to the aged Major General John Wool, commander of the fortress and a veteran of the War of 1812, and offered to lead a boarding party to sink the ship before it could leave the yard. Like Army officers before and after in Hampton Roads, Wool demurred. Sinking ships, even attacking warships, were what navies did.

Osbon, dismissing Flag Officer Louis Goldsborough, the senior Union Navy officer, as overly cautious, did not pursue the matter with him. If he had probed, Osbon would have learned that the blockade commander had warned Washington that “she will, in all probability, prove to exceedingly formidable,” especially if accompanied by fast-moving shallow-draft gunboats.

--------------

In the winter of 1861-1862, more and more naval officers in Hampton Roads wanted the Army to destroy Merrimack before it could threaten the Union’s tenuous control of Hampton Roads by re-taking Southside Hampton Roads. McClellan, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, eventually received the Navy’s proposal to attack the port of Norfolk and the Gosport shipyard in Portsmouth, but, like Wool on the scene, did nothing with it.

Congress and sloop Cumberland paid the price for these months of dithering. They were the first ships sunk by Merrimack, now christened CSS Virginia, in the Battle of Hampton Roads in March, 1862. Commander William Smith, who had turned over command to Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith a few days earlier, was still on board when Merrimack attacked. Congress was only able to fire two of its stern guns in its defense. It didn’t slow the ironclad down. When Lieutenant Smith was killed in the fighting, Commander Smith ordered Congress’ colors struck at 4 p.m. The frigate had been engaged with CSS Virginia for about 30 minutes.

The threat that Smith had been forced to ignore to defend against mine attacks remained a menacing force even after John Ericsson’s Monitor battled the Confederate ironclad to a draw. The Union Navy in Hampton Roads and in Washington were now frantically searching for any way to rid themselves of this enemy. It did not appear likely that Monitor was capable of sinking Virginia; and as long as it was able to fight the wooden ships of the Union Navy in Tidewater Virginia were in great danger.

A little more than a month after the battle and as the Union Army was descending on Tidewater in preparation for the Peninsula campaign, lawyer and self-described patriot, H.K. Lawrence offered Welles his ideas on how to sink the Confederate ironclad and two other Confederate vessels, Jamestown and Yorktown, at the naval shipyard. With those three vessels out of action, the Union Navy would control Hampton. Roads. At first he put the prize money he wanted for sinking the ironclad at $500,000 and the two smaller steamers at $100,000 each.

Although the price was high, Welles was interested.

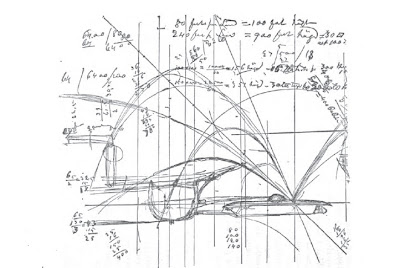

If the Confederates could use submarine explosives to destroy ships so could the Union, Lawrence wrote. He first proposed receiving 2,000 pounds of gunpowder, later reduced to 1,500 pounds, to build “four submarine armors” at the Washington Arsenal at a cost not to exceed $1,800 and in unspecified ways to ship those “armors” to Fortress Monroe and from there to destroy CSS Virginia by May 9. The attacks on Jamestown and Yorktown were dropped in later correspondence, and Lawrence reduced the suggested prize for sinking the ironclad to $100,000.

Still unanswered in the correspondence were any details of how the attack was to be carried out. He likely either intended to float the mines toward Virginia and have them explode on contact or draw close enough to it to place the explosives under the ironclad to detonate them electronically.

Welles was considering Lawrence’s plan out of desperation. He knew his wooden ships were no match for the Confederate ironclad, and the Monitor was doing all it could to protect the troop build-up. Yet even knowing all that, Union Army commanders ignored the threat Virginia posed to all their operations in Hampton Roads.

Finally, at President Abraham Lincoln’s personal insistence after he surveyed the Confederates’ hold on Southside Hampton Roads from the water, the Union Army moved on Norfolk and Portsmouth May 10.

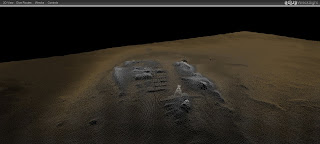

Reeling from the long-delayed attack, the Confederates scuttled Virginia and Confederate States (one of the Navy’s six original frigates) off Craney Island because they had too deep a draught to go up the James River to safety in Richmond and burned Germantown, Plymouth, Jesup, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and William Seddon.

From July, 1861 through May, 1862, Union Navy officers had been pre-occupied with defending themselves against a mine attack or how to use mines to destroy the Confederacy’s great warship with mines before it could strike again. Within weeks, they were confronting new mine threats past the Curle in the James River, just below Richmond. The mine ranges set in the water close by large gun emplacements on Drury’s Bluff and the south bank and Chaffin’s Farm on the north were effective and deadly. Unlike New Orleans, the Union Navy even with its attack gunboats never succeeded in taking Richmond from the river.

Lawrence’s scheme to sink Virginia as bold as it seemed in letters and as desperate as it would have been in practice had been overcome by old-fashioned events.